One summer when I was a kid, my family went to a state park to go camping. While there I was able to go on a wild edible nature hike with a guide. For me, that is by far the best way to learn and I may look into doing something like that again. Until then, the websites I linked in Three Wild Edibles That Are Good to Know are a great resource. That’s not handy when you’re actually out foraging. For that reason, books are a great resource to have on hand, of which I have a few.

Some of the books I’ll mention are for my geographical region but if you follow the link you should be able to find your region in the related subject area, or in the “What others who bought this book are buying”. A lot of the plants will overlap regions, but not all.

A Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants: Eastern and central North America (Peterson Field Guides)

This book is crammed full of information in a textbook-like manor. It lists the name of the plant, the states it can be found in as well as the type of habitat it can be found in. The time of year that it flowers or ripens is listed and common uses such as salads, cooked greens, pickled, etc., are also given. There are many poisonous plants listed. In some cases it is pointed out “use caution as the poisonous plant looks similar to another plant”, listing the resembled plants.

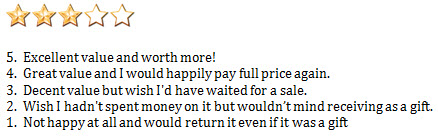

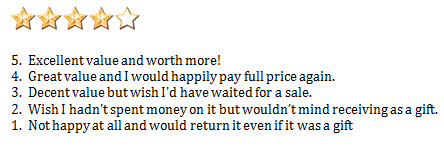

The pictures of the plants are drawn in black and white; they’re very well done, but still drawn. There are around 15 pages of color photos, one sided and 4-5 images per page. The lack of color photos is the only downside this book really has, but it’s a big one to me. However, there is enough great information on a huge number of plants to still make this worth buying. I give this book three stars.

A Field Guide to Medicinal Plants and Herbs: Of Eastern and Central North America (Peterson Field Guides)

This is also crammed full of a huge amount of information in a textbook-like manor. It lists the same type of information on plant name, location in the region and the habitat it can be found in.

In many cases the minerals and other nutrients are listed. The traditional method used to prepare by various cultures, such as a tea and poultice is often listed. Also listed is the ailment it is used as treatment for. Poisonous plants are listed as well, sometimes a vague warning and others a specific warning of what to avoid.

This book is loaded with pictures; most pages have at least 2-3. This book is a good one if you’re looking to add some of the medicinal properties of these plants to your diet, but don’t look to them to replace your medicine and be sure to consult your doctor.

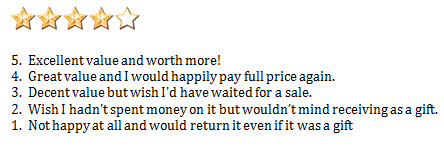

This book’s approach is to identify medicinal plants, so there isn’t information on how to prepare the plants as food. For foraging I don’t think this is a standalone book. I do, however, highly recommend it and give it four stars.

Wild Berries & Fruits Field Guide of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan

This book has the typical information you would expect; the geography is already listed to three states (there are more books available for other states). It covers the habitat it can be found in and the time of year the fruits and berries will be ripe.

There is a notes section that details interesting facts about the plants. Some of this will include medicinal uses and some list the type of animals that eat it.

There are many color pictures and a very nice in season and out of season pictures section. This is huge, as many plants look very different in the various seasons.

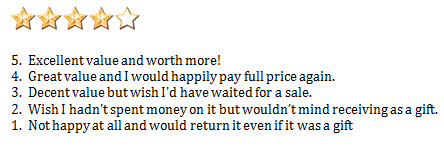

If you want to forage for wild fruits and berries, I highly recommend a book like this based on your geography. I give this book 4 stars.

Stalking The Wild Asparagus

This is one of the first, if not the first book on wild edibles. Where the other books offer a lot of information in a technical type manual, this book gives a lot of information but has more of a feel of coming from a grandfather on a nature hike. The author does a wonderful job explaining the plants’ history. He also spends a fair amount of time explaining different ways to prepare the plant. While there are a few drawn pictures, the books aim isn’t to teach you to identify the plant, but to know the history of it and even have an appreciation for it. Where the other books of this type might give a paragraph or two on a plant, most plants are given multiple pages in this one. The dandelion, for example, was given six pages.

There are fewer plants covered, still numbering around 45. He also covers how to cook carp, crawfish and a few other similar topics. If foraging is a passion, I highly recommend this book. I give it four stars.

Here are two books that I do not own, but are on my want list.

The Forager’s Harvest: A Guide to Identifying, Harvesting, and Preparing Edible Wild Plants

This book is 512 pages and covers 41 plants in depth with multiple color photos.

If you have another book on the subject, please list it in the comment section.